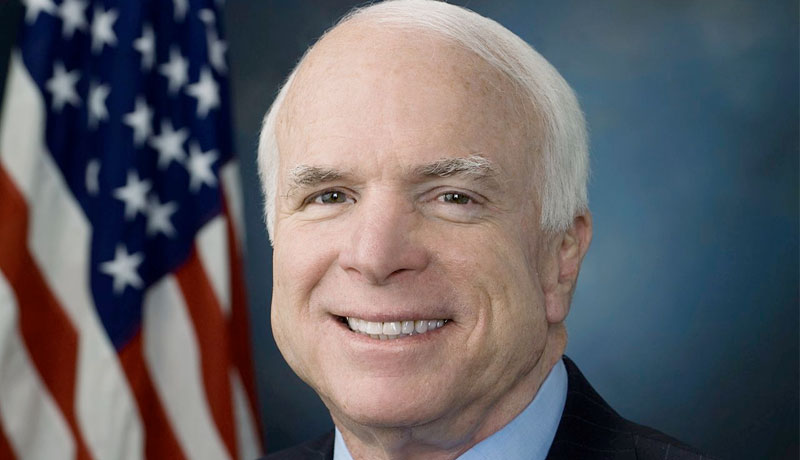

On the day the news broke, it led all media reports, including the front page of The New York Times. John McCain, who has served in the Senate for 30 years representing Arizona and a two-time presidential candidate, received a diagnosis of glioblastoma, a lethal form of brain cancer.

McCain died the next year, in 2018, after a battle with this highly malignant brain tumor. It was only one day after it was announced that the senator had decided to discontinue treatment.

John McCain’s Brain Cancer: Glioblastoma Tumor

John McCain’s brain tumor was diagnosed in mid-July 2017 when a blood clot above McCain’s left eye was discovered during a routine physical exam.

The clot was removed by doctors at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, where McCain received treatment. It was later determined that it was associated with glioblastoma.

John McCain’s Melanoma

McCain’s last bout of melanoma was in 2000. He previously had three other melanomas; all four were found at stage zero. He was diligent about his skin check-ups every four months following his melanoma diagnosis.

Despite later developing a brain tumor, there is likely no correlation of his prior melanomas to his brain cancer.

How Did John McCain Die?

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is a tumor that originates in the brain, not as the result of other cancers. It is also an aggressive form of cancer.

John McCain died at age 81 on August 25, 2018, just over a year after his first diagnosis. He was surrounded by his wife and family, who had reported the day before that he had decided to end treatment.

The Cause of John McCain’s Death: About Glioblastomas

Glioblastomas, which are made up of astrocytes, star-shaped cells in the brain and spinal cord, are generally highly malignant. These tumors usually develop in the cerebral hemispheres of the brain, but can also be located anywhere else in the brain or spinal cord. Glioblastomas are very aggressive and tend to form and become evident very quickly. Like many other cancers, the exact cause of glioblastoma is unknown.

According to the American Cancer Society, the five-year survival rate for glioblastoma is about 6 percent for patients over age 55, although many patients do not make it past two years. However, while progress is limited, it is still present. Thirty years ago, a scant 1 to 2 percent of patients lived longer than two to three years with this cancer.

Glioblastoma strikes up to 10,000 people a year, and most notably those numbers connect John McCain to other national political figures. The late acclaimed Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts was diagnosed with a glioblastoma in May 2008 following a seizure and died in August 2009. Beau Biden, the late son of President Joe Biden, died in 2015, two years after being diagnosed with the same brain tumor.

Brain cancer such as glioblastoma is especially difficult because of its location. The brain is protected by the blood-brain barrier, a thin membrane that surrounds the brain. If foreign bodies enter, there is almost no immune system (T cells) to fight them. That’s because other parts of the body rely on a healing immune reaction, triggering inflammation. That inflammatory process does the fighting, but there’s no room in the brain/skull for that inflammation. So, cancer cells enter a fairly defenseless and yet vital organ.

McCain’s Symptoms

Symptoms of glioblastoma vary depending on the location of the tumor in the brain. They can include persistent headaches, blurred vision, memory loss, personality or mood changes, and/or seizures.

John McCain’s signs were typical; he told doctors that at times he felt foggy and experienced intermittent double vision.

Treatment Options for McCain’s Brain Cancer Type

Despite new treatments for cancerous brain tumors on the horizon, and hopes for better solutions, there has been no significant medical advances beyond the current standard of care. This entails surgery (if possible) to remove as much of the tumor as possible, followed by a regime of chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments. After a break in that treatment, a subsequent more extensive continuation of chemotherapy might occur.

However, one reason brain tumors are so tough to treat is that many drugs cannot efficiently enter the brain to act on the tumor. The unique barrier, the “blood-brain barrier,” limits the passage of molecules, like many chemo drugs, from the bloodstream into the brain. Many drugs that may block glioblastoma growth in the lab simply do not work effectively in patients because of this barrier

On top of that, even if chemotherapy were to achieve a 90 percent kill-rate, the other 10 percent of cancer cells still march on and quickly replicate. Those cancer cells reproduce quickly in the brain, due to the organ’s vast network of blood vessels.

The tumor that results isn’t a round, definable mass, but instead those malignant cells, which usually arise from the astrocytes (the star-shaped cells of the central nervous system), branch out like tentacles throughout the brain.

The bottom line: in the brain, cancer becomes pervasive, and every part of that brain serves a vital life function. So, we are left with that “standard of care,” as it is formally called, to do a pretty difficult job.

Other Types of Treatments

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that entails utilizing the body’s own immune system to recognize and target the cancer. This function is similar to how the immune system fights infections and other diseases. The medical community is particularly excited about immunotherapy-based treatments for glioblastoma, which together with vaccines and other targeted therapies, is the subject of clinical trials being conducted across the country. According to the National Institutes of Health’s clinical trials database, more than 300 glioblastoma studies around the U.S. are active or recruiting.

Chemotherapy and radiation are most responsive treatments for the types of glioblastoma that usually occur among a younger population. However, in relation to Senator McCain, the types of tumors identified to be responsive to immunotherapy often occur in older people.

This is also the case for those who have a genetic profile that results in tumors with many mutations. This creates a situation with various different antigens (which spur an immune response) that are recognized by immunotherapy.

Vaccines

As a general category of treatment, vaccines are similarly meant to treat cancer by strengthening the body’s natural immune system response against the disease. Back in 2015, big news resulted from a 60 Minutes broadcast story on the use of a modified poliovirus treatment for glioblastoma, an experiment done at Duke University that showed early signs of success. This research remains ongoing.

Clinical Trials

The purpose of clinical trials is to test the most promising new treatments. Clinical trials are conducted in a series of steps, called phases; each phase is designed to answer a separate research question. There are three distinct phases, each of which focuses on details of the treatment: Phase I (the dose), Phase II (the safety), Phase III (how well the treatment works).

Trials have specific criteria based on scientific reasoning. Eligibility is decided on various factors, such as the exact tumor type, type of treatment already administered and other general health issues.

Participating in a clinical trial entails both benefits and risks. However, patients must meet the criteria for a particular study in order to become part of a clinical trial.

At ANA, we avidly follow the news of stories like John McCain’s. His story inspires us to provide a general understanding of brain tumors, an area in which we have worked for decades.

ANA is a team of expert neurosurgeons and medical professionals, who combine their decades of knowledge to provide information, events, and articles on a range of neurological conditions.